Aussie Jobs Growth Approaches Stall Speed

Just 85k new jobs in the past 9 months

For a long time here at Burnout Economics we have been watching for signs of Australian labour market weakness.

But for significantly longer than many expected it did not come. I made the case on several occasions that weakness in the ABS Labour Force Survey was a case of sample rotation issues and seasonality.

The passage of time would prove those conclusions to be correct and that the Australian labour market found itself in some rather unique conditions, particularly from a historical perspective.

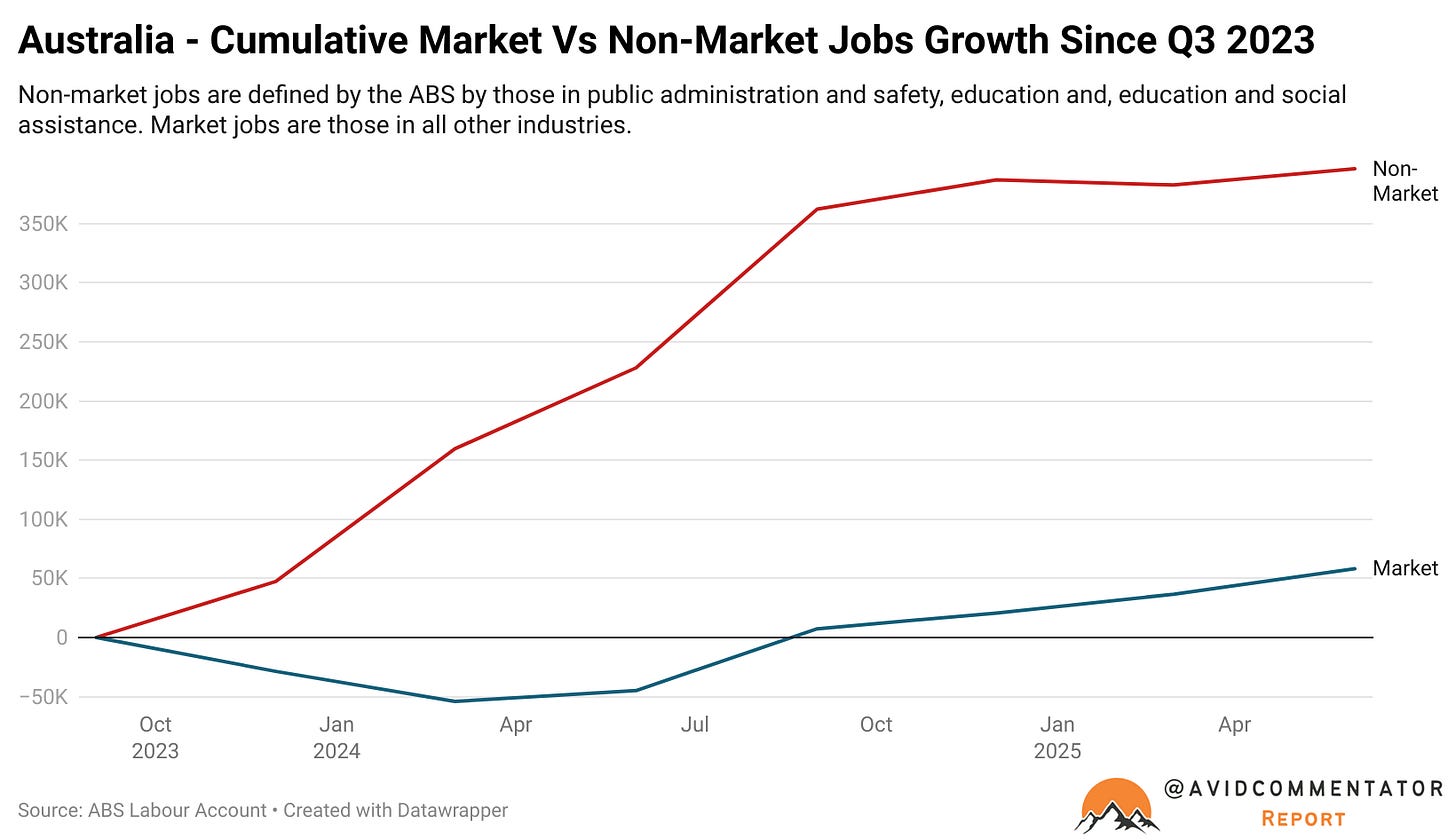

In short, in the years since the election of the Albanese government and the conclusion of the positive impulse from pandemic driven stimulus and revenge spending, the Australian economy has become increasingly reliant on so called non-market jobs.

Non-market jobs are defined by the ABS as those in Public administration and safety, Education and, Healthcare and social assistance.

From the third quarter of 2023 onwards in particular, they took over as the driver of the overwhelming majority of employment growth.

But now non-market jobs growth has slowed to a crawl, with Deutsche Bank recently describing it as a “collapse”.

The big problem for the Australian economy going forward is that so far the market sector of the economy (all other sectors of the economy excluding those defined as non-market) has not refired sufficiently to create an adequate number of jobs to keep unemployment from rising, which is the scenario the Reserve Bank was resting much of its hopes on.

The latest ABS Labour Account data provided further fuel for concern, revealing that just 35,300 jobs were created in the June quarter.

This marks the third straight quarter of weak jobs growth, at least relative to the still highly elevated rate of working age population growth, with just 11,500 jobs created in the March quarter and 38,000 jobs in the December quarter of last year.

Across the last three quarters of data combined a total of 85,000 jobs were created in net terms, while the working age population has expanded by over 337,000.

Why?

The clear risk of higher unemployment presented by those figures has left many wondering how unemployment isn’t rising more significantly already.

In short, it comes down to the type of jobs being lost and how employment is measured by the Labour Account and Labour Force Survey.

In the Labour Force Survey, it counts the number of people employed or unemployed.

In the Labour Account, the data is of a more granular nature and generally of a higher quality.

Amongst other things, the Labour Account counts the total number of jobs currently filled within the economy.

This leads to more jobs being counted than people, illustrating the total strength of jobs growth, but not necessarily the balance between employment and unemployment.

Currently the jobs that are being lost within the economy are largely second jobs, while the number of people who are employed overall continues to rise.

A Warning?

The big question going forward is, is this deterioration the beginning of a greater deterioration in the labour market or is it merely a redeployment away from multiple job holders.

Looking at a chart of the headline unemployment rate, one can’t help but have at least a degree of concern.

One of the major issues going forward could be to what degree will the labour force grow.

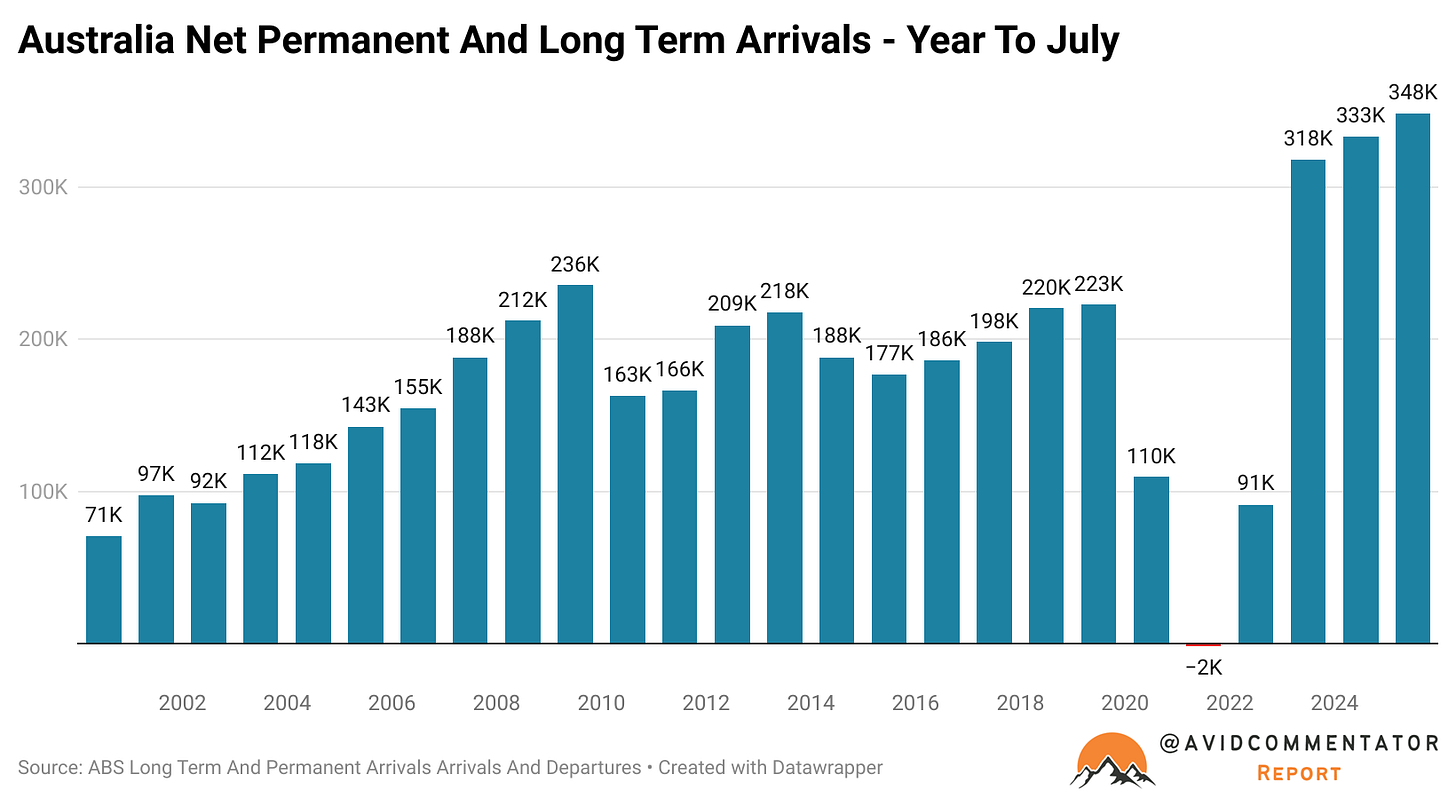

The expectation of Treasury and private sector commentators such as the Commonwealth Bank is for labour force growth to continue to trend down as migration continues to moderate.

But there may be a rather significant issue with that outlook. It’s possible that migration may be reaccelerating.

According to the ABS net long term and permanent arrivals figures, the year to date up until the end of July has seen the largest figure in the history of the data series.

While this is far from a 1 for 1 proxy for net overseas migration, it has been used by the federal government’s Centre for Population as a broader indicator of where migration levels could be going on a longer term time horizon.

Going Forward

Given that whatever settings that will decide Australia’s migration intake in the coming quarters have already largely been baked in, the fate of the nation’s labour market may be in the hands of the consumer economy.

The hope is that it will refire, amidst the end of the so called “crowding out” by non-market sector pulling in workers from other sectors of the economy.

Whether whatever boost that could be had will be adequate to support the labour market remains to be seen, particularly if labour force growth does see a resurgence.

On a longer term time horizon, there is the potential for a response from fiscal policymakers to fire up the taxpayer funded jobs printer and yet again begin to paper over the cracks in the nation’s labour market, as it has for a sizable proportion of the time since the Global Financial Crisis.

Ultimately, Australia may be approaching a major inflection point in the nation’s economic cycle.

— If you would like to help support my work by making a one off donation that would be much appreciated, you can do so via Paypal here or via Buy me a coffee.

If you would like to support my work on an ongoing basis, you can do so by subscribing to my Substack or via Paypal here

Thank you for your readership.