How Long Can Australians Keep Spending And Keep Inflation High?

Equity withdrawals, savings and consumer credit this article covers it all

In the United States overnight, the Bureau of Economic Analysis released the personal consumption expenditure data for October. The data revealed that the spending of Americans had risen by an inflation adjusted 0.5% in October.

The relative strength of U.S consumers in the face of rising interest rates and the highest inflation in decades continues to surprise analysts.

However, the reasons behind this are rather clear, as the graph below from Zero Hedge illustrates nicely. Credit card usage has surged, with balances continuing to hit all time record highs, while at the same time the personal savings rate has collapsed to sit at just 2.3% from a level of around 9% prior to the pandemic.

On paper there is still a great deal of fuel for Americans to expend excess savings and run up credit card debts, but these aggregate figures gloss over the fact that many Americans have run out of scope to keep up with the rising cost of living.

But for the moment, that doesn’t seem to matter to the economy, with aggregate consumer spending continuing to perform well enough, particularly given the circumstances and growing speculation of a recession brewing on the horizon.

Now we have got a bit of background on how an economy can continue to drive inflationary pressures based on credit and savings we can move on to the crux of the article, how long Australians can keep up their spending based on savings and credit.

‘Equity Mate’ Uniquely Australian Twist

Before we kick off, its worth noting that there is another factor in Australia that is far less significant in the U.S, home equity withdrawals.

As of the year to June 2021 (the latest available data), Australian’s withdrew $93 billion (4.65% of GDP) from their mortgages to fund all manner of expenditure, holidays, home renovations and cash injections into small businesses.

To put this into perspective, according to data from Black Knight, during 2021 Americans withdrew $275 billion (1.13% of GDP) in home equity. Prior the global financial crisis, home equity withdrawals as a percentage of GDP peaked at 2.65% at the end of 2005.

This is an extremely significant driver of Australian household consumption. In 2019-20 total personal income was $983 billion. So the extra $93 billion flowing into household coffers provides a major boost.

Yet despite rising rates historically causing U.S home equity withdrawals to peak, in Australia the data that is available suggests that this is not the case. According to data from research firm Digital Finance Analytics, the proportion of Australians choosing to withdraw equity when externally refinancing (refinancing with a different lender) is at all time record highs.

For those of you wondering about more up to date data, I have asked all the relevant agencies, but they have not shared it as of the writing of this article. If that changes I will do an update and post it on Twitter.

Credit Cards

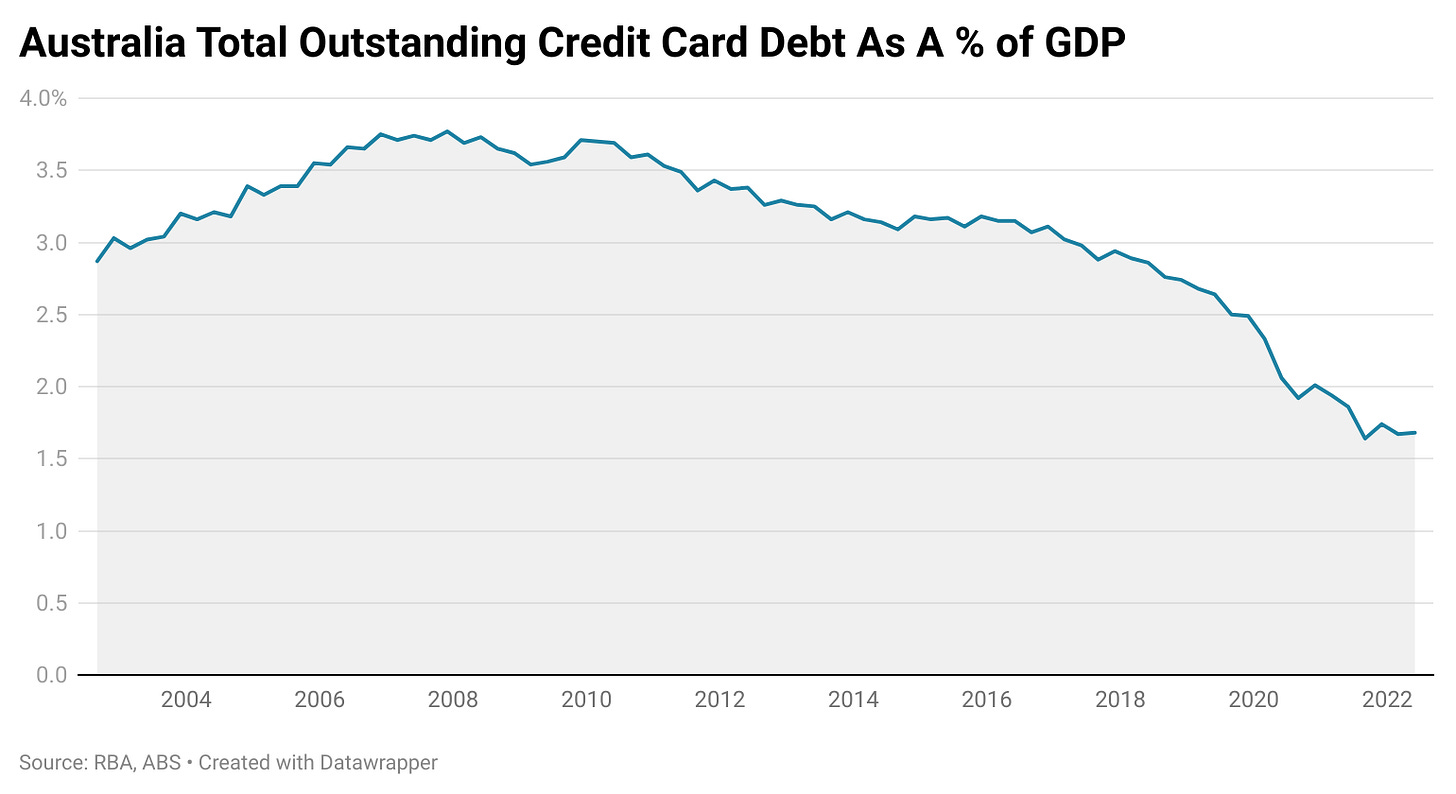

If Australians were to follow the example of their American compatriots, there is plenty of scope for them to expand balances and for them to remain well below record high’s relative to GDP.

To put this into perspective, total revolving consumer credit balances in the United States amount to 4.52% of GDP.

Its worth noting that this provides a somewhat distorted perspective. Australians have increasingly used credit cards to take advantage of interest free periods and various reward schemes. Once you start looking at the total aggregate balances that accruing interest, it becomes clear that there is a great deal of scope for Australians to turn to credit cards to keep up their spending.

In 2012, balances accruing interest as a percentage of GDP topped out at 2.24%. For Australians to reach this same level now, they would have to add over $30 billion to their collective credit card balances which are accruing interest.

So the scope is very much there for Australians to continue to spend using credit cards and home equity withdrawals, but it comes down to whether or not they choose to.

A Healthy Pile Of Savings In Aggregate

In Australia there is no sign of household savings rates falling below their long run average and they remain well above the 5 year average recorded prior to the pandemic, 8.7% vs 5.7%.

Meanwhile, the rolling 12 month increase in household bank deposits remains 132% higher than where they were prior the pandemic, suggesting that there is plenty of scope for savings levels to decrease and instead be spent within the consumer economy.

If Australians were to revert their household savings to 2.6% of GDP as they were prior to the pandemic, they could spending an additional $67.7 billion per year on consumption.

A Challenging Conclusion

Theoretically, if the only change to occur was household savings habits returning to pre-pandemic norms, Australians could continue to accelerate their consumption to keep up with the rising cost of living and rising interest rates.

Based on data from the Reserve Bank, by the time the most recent rate rise is priced into mortgage rates, the annual interest bill for mortgage holders would have risen by $47 billion. While this is an enormous sum of money, it is also $20 billion a year less than the aggregate increase in GDP adjusted household savings since which has occurred since the pandemic began.

Once you add home equity withdrawals and credit fuelled household consumption to the mix, it becomes clear that household consumption could continue to remain strong for the foreseeable future, even in the face of rising inflation and higher interest rates.

It should be emphasized that this is based on aggregate figures. Some Australian households have already been driven to wall by rising interest rates and high inflation. However, as the situation in the U.S has illustrated, that is not the main driver inflationary pressures or overall household spending, aggregate demand is.

But ultimately, the big question is will Australians choose to keep spending, taking on greater levels of credit card debt and return their savings patterns to pre-Covid norms.

That is an extremely challenging question to answer with any degree of certainty, but it should be enough to be a cause of concern for the RBA. If Australians choose to pursue the same path of savings and credit fuelled consumption as their American friends across the Pacific, it could be a quite a long time before rate rises have the desired effect.

— If you would like to help support my work by donating that would be much appreciated, you can do so via Paypal here or via Buy me a coffee. Regardless, thank you for your readership.

If you would like to support my work on an ongoing basis, you can do so here via Patreon or via Paypal here

Really good balanced piece mate, paints a picture for me that there is a lot of uncertainty in the future and that managing the economy will be tricky for the RBA and government.