Is Australia's Economy About To Hit A Wall?

Warning Lights Are Flashing For The Aussie Labour Market

When the December ABS jobs report was released in mid-January, it made for fairly bleak reading, at least in seasonally adjusted terms. In aggregate 106,600 full time jobs had been lost, with the headline figure moderated by the addition of 41,400 jobs, for a net loss of 65,100. Monthly hours worked fell by 10 million or 0.5% and the participation rate fell from 67.3% to 66.8%.

All in all, an absolutely disastrous print for the Australian labour market. Outside of the pandemic, the nation’s economy had never lost this many full time jobs. When adjusted for the size of the labour force, outside of the pandemic this level of job losses had only occurred twice before, at the height of the 1982-1983 recession and the 1990-1991 recession.'

Given the volatility in seasonally adjusted job creation, I removed the seasonal adjustment from the equation and used the raw figures from the ABS data. Solely looking at December’s since the current ABS data set began in 1978, it was the weakest level of month on month job creation since 1982 (ex-pandemic).

However, looking at the job creation figure for December 2022, when the labour market was still unequivocally strong, its clear that an element of changed seasonal hiring is distorting the figures, at least somewhat.

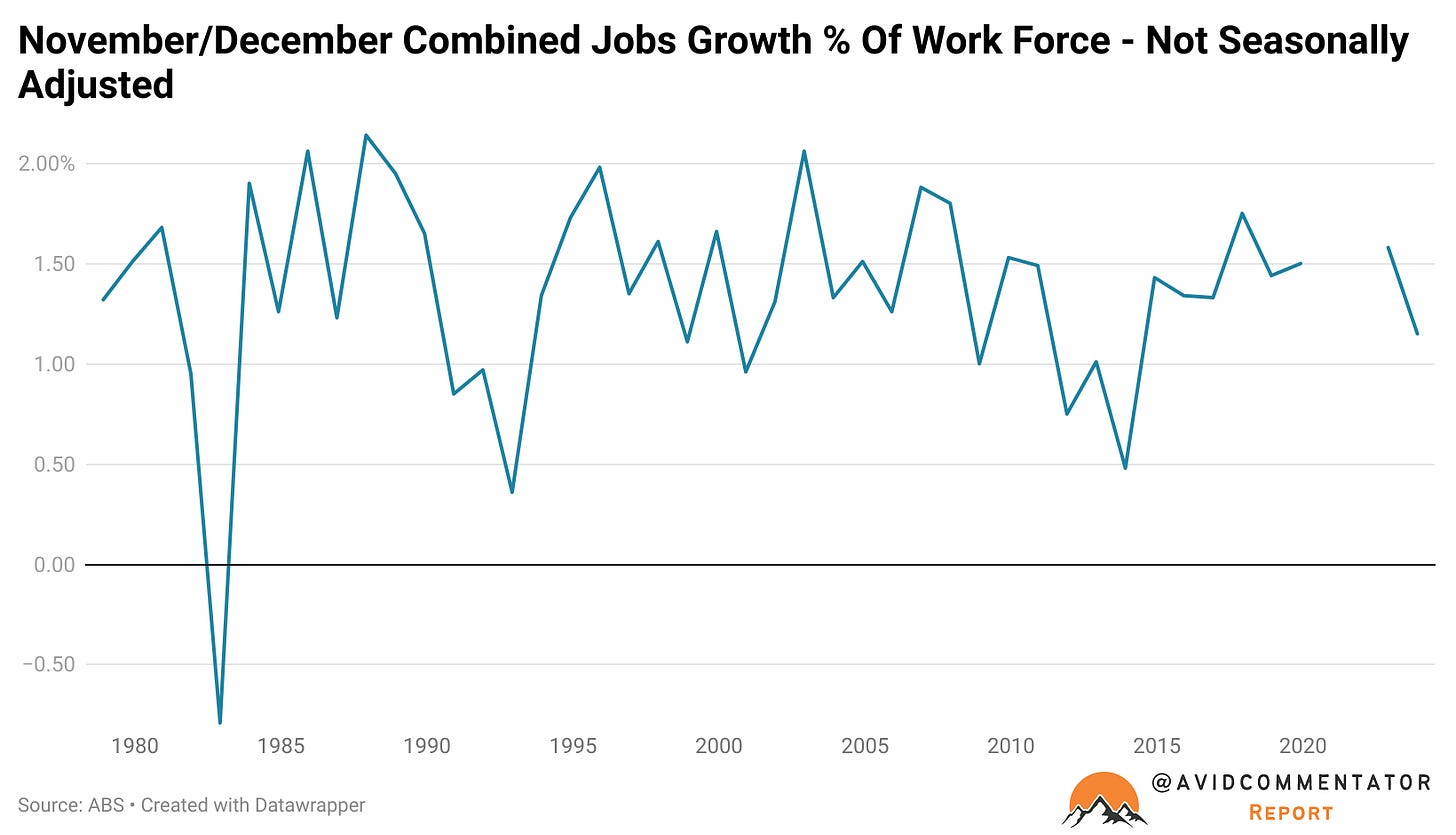

In an attempt to counter this, I combined jobs growth for November and December into a single metric. On this number the performance was better, but still produced the weakest holiday season jobs growth since 2014.

Based on these numbers so far, one can conclude that jobs growth has deteriorated significantly, but seasonality may be masking precisely to what degree.

The Final Arbiter - Hours Worked

In order to get a better idea of underlying demand for labour and to smooth out some of the seasonal issues, we’ll be looking at hours worked in trend terms.

In December 2022, the economy recorded a 1.57% increase in hours worked vs one quarter earlier in September 2022. In December 2023, the same metric recorded a fall in hours worked of 0.65%.

Its worth noting that this is not a seasonal issue, hours worked have been declining since August based on comparing the current month with the month of one quarter earlier. In fact, the deterioration was almost as great in November as it was in December, suggesting that even with whatever seasonal distortions made it through the ABS’s trend smoothing were not a significant factor.

While a 0.65% drop in hours worked on this basis may not sound like much, it has only happened in three previous cycles excluding the pandemic, in 1982, 1990 and 2008. 1982 and 1990 both resulted in very challenging recessions and in 2008, recession was avoided, but unemployment still rose significantly.

To illustrate how different this cycle has been compared with the aforementioned ones in the past, the rise in unemployment peak to trough over the 12 months prior to this point being hit were contrasted.

Over the various cycles unemployment rose by an average of 1.17 percentage points, experiencing the largest rise in 1990 (+1.4 percentage points) and the smallest in 2008 (+0.9 percentage points).

Considering that unemployment has only risen by 0.4 percentage points in the current cycle amidst the largest labour force growth on record, suggests that so far Australia has been remarkably lucky.

Things Could Go South Fast

According to a recent analysis by CBA, the economy needs to create around 32,200 jobs per month for unemployment to remain stable. On the other side of the coin, in trend terms the economy created 18,800 jobs in December.

If we were to assume that the participation rate remained static along with labour force growth and jobs growth, unemployment would rise to 4.3% by June and 4.8% by the end of 2024.

With labour force growth expected to remain extremely high throughout the year, the risk is that a moderation in jobs growth could drive an even larger increase in unemployment quite swiftly.

Its worth making the distinction that this is based on not a single job being lost in net terms. If even 100 jobs were lost each month in net terms during 2024, we would close out the year with an unemployment rate north of 6%.

The Takeaways

So far the reticence of employers to let go of staff like they would have under similar economic conditions in past cycles has prevented a swift rise in unemployment. This is arguably due to the pandemic, stimulus fuelled consumption and the shortage of labour that followed.

In this, Australia is not unique, many nations have seen weak real economic outcomes, yet so far job losses have been remarkably limited.

But where Australia is relatively unique compared with its developed economy peers, is its level of labour force growth. It won’t take a recession or net job losses to see a large expansion in the unemployment line.

Ultimately, even a small deterioration in jobs growth from those seen in December will see unemployment rising much more strongly than consensus forecasts. But a stalling or even reversing level of jobs growth could see the labour market hit the wall.

With employers holding onto what is now excess labour, even in the face of falling hours worked, there is a risk that normalizing employer attitudes could drive a swift rise in unemployment.

— If you would like to help support my work by making a one off contribution that would be much appreciated, you can do so via Paypal here or via Buy me a coffee.

If you would like to support my work on an ongoing basis, you can do so by subscribing to my Substack or via Paypal here

Does the ATO release single touch payroll data ? Or is that what the ABS data is based on ? The STP data would be pretty accurate and timely. I need to submit every month for my business.

Everybody is going to hit the wall ... very soon ...

https://windowsontheworld.substack.com/p/goldfish-wisdom